The Best Algorithm Ever

Theoretical computer scientists spend a lot of time thinking about the asymptotically optimal algorithms for various problems. For instance, as of writing this post the asymptotically best known algorithm for multiplying two $n \times n$ matrices over a field runs in time $\mathcal{O}(n^{2.371552})$. What this means is that, for some constant $c$, the algorithm always takes fewer than $cn^{2.371552}$ steps to compute the answer on $n \times n$ matrices. The reason we’re not worried about the specific value of $c$ is because, as $n$ gets really big, it stops being the important thing – if we have one algorithm running in time $5 n^2$ and another algorithm running in time $5000000 n$, then as soon as input size gets bigger than $1000000$ the second algorithm becomes better. Of course, when it comes to solving actual problems with actual computers, it may be that you never need to deal with inputs of size more than $1000000$, and so the first algorithm is always better in practice.

This kind of story is true with matrix multiplication – the $c$ in $cn^{2.371552}$ is so large that the input size would have to be orders of magnitude larger than all the data stored in every computer on earth before the algorithm became faster than the straightforward $\Theta(n^3)$ algorithm. Even so, I think the fact that there exists an $\mathcal{O}(n^{2.371552})$ time algorithm for this problem really does say something meaningful – after all, even if I would never need to work with them in practice, I can imagine having to multiply ridiculously huge matrices. The fact that this is possible to do with far fewer than $n^3$ steps suggests some kind of inherent structure to the problem that you might otherwise suspect didn’t exist (and indeed seems likely not to exist in matrix multiplication over other algebraic structures). Regardless of your philosophical interpretation of asymptotic complexity, the fact remains that if a paper was published tomorrow titled “A Matrix Multiplication Algorithm With Provably Optimal Asymptotic Time Complexity”, it would get a lot of attention.

But what if I told you that, for the vast majority of problems algorithms researchers think about, we actually already know the (asymptotically) best algorithm? This sounds at first like a really incredible claim. Maybe after I explain it will sound less incredible, but I still think it’s an important observation.

For a concrete example, let’s look at the problem of integer factorization:

Integer Factorization Problem: given an $n$-bit integer $x$, return $x$’s list of prime factors.

This problem is interesting because it’s something where we can verify a solution efficiently (multiply together all the proposed factors and check if the result equals $x$, then use fancy number theory algorithms to efficiently check that all those factors are prime). However, we have no idea if it’s possible to produce a solution efficiently – whether or not this problem is solvable in polynomial time is unknown.

In 1973, Leonid Levin noticed that all problems of this form have a simple algorithm 1. The basic idea is: the length of the optimal program is some constant independent of $n$, so if we just want to be asymptotically equivalent to it we can try running all programs in increasing order of length and check their outputs. After a constant number of tries, we’ll simulate the optimal algorithm, which will print out the correct factorization and solve the problem.

I’ll walk through this idea carefully in case you haven’t seen this kind of thing before. Suppose we iterated through all strings in alphabetical order. Most of these are nonsense (things like “a3sarth&au%!”, “eiudyot78”, or “0 is not a natural number”), but some of these strings will be valid python (or C, or Haskell, or Turing machine code – substitute what you like here) programs:

def sillyfunction(x):

x = "this is a string of characters that just happens to be a valid python program."

return x

print (sillyfunction(x) + " if we enumerate over all strings we'll hit it eventually.")

If we start iterating through all strings in alphabetical order and trying to run a python interpreter on them, some of them will return an output – we can then check the output, and if it’s a solution to the factoring problem we’re done! The issue with this approach is that some short program might run for a really long time – perhaps even just loop forever – and so if we just tried simulating programs in order we might never simulate the “right” algorithm. The workaround is: run all possible programs in parallel, allocating exponentially less time to alphabetically later programs. That is:

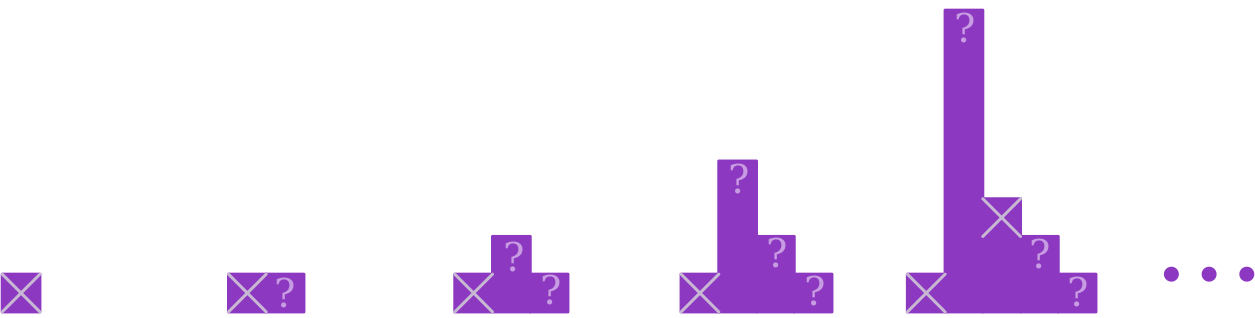

Levin’s Universal Search: On the $i$th “stage”, simulate up to $2^i$ steps of the first (alphabetically) program, $2^{i - 1}$ steps of the second program, on to $2^0 = 1$ step of the $i$th program. Whenever one of these programs finishes, check it’s output to see if it’s the prime factorization of $x$; stop when you’ve found it.

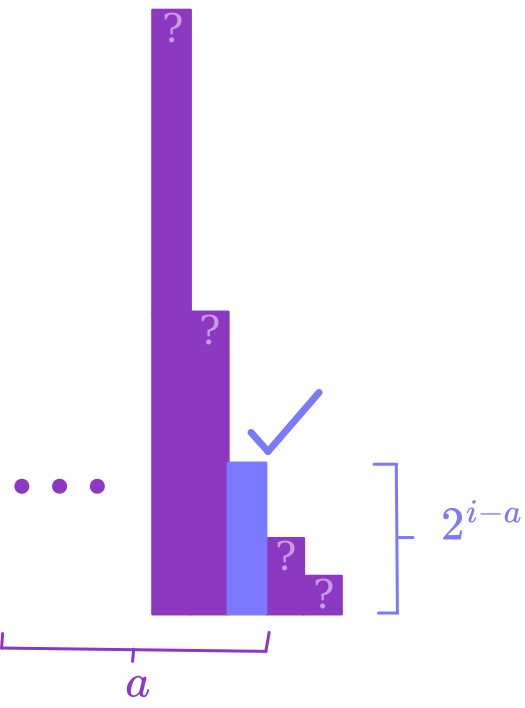

This algorithm might seem ridiculous (and I suppose it is), but it’s also kinda nice. Suppose there is some algorithm $A$ that solves the factoring problem in $t(n)$ timesteps (for concreteness, imagine it runs in polynomial time). If we write down the code for a python implementation of $A$, that string will correspond to (say) the $a$th string in alphabetical order. If you look at how long this algorithm takes until it simulates the $a$th string for $t(n)$ timesteps, the answer should be something like $2^{a} \cdot t(n) + a \cdot v(n)$, where $v(n)$ is the amount of time to verify the outputs (in the case of factoring, we can do this with a known small polynomial algorithm – we’ll assume this is a lower order term).

Notice, though, that $a$ is not a function of $n$ – it’s just a function of the string representation of the python program, which is some constant not depending on $n$! So, if $A$ solves factoring in time polynomial in $n$, then Levin’s algorithm also solves factoring in polynomial time. In fact, assuming the optimal algorithm for solving the problem is slower than the verification procedure we’re using, Levin’s algorithm runs within a constant factor of the true optimal runtime. So, although we have no idea how fast it actually runs, we know the asymptotically optimal algorithm!

If you’ve ever tried writing down an algorithm, you probably know that they usually take more than one or two characters to describe. And if your python code is even just a couple lines, you’re going to end up with like $2^{1000}$ alphabetically earlier strings. If you’ve ever tried using a computer, you probably know that $2^{2^{1000}}$ is only very technically a constant. Certainly nobody is ever running this code, not even if you’ve got lots of RAM or a really fancy GPU or whatever. But hey, it’s a constant! And what’s more, it’s clear that this algorithm isn’t just applicable for factoring – it should work for any problem where we have a fast way of checking solutions2.

This is the algorithm that Levin described. At this point you will probably protest, “Is this really the best algorithm ever? Such a big multiplicative constant is frankly ridiculous – and besides, you claimed it could solve basically every problem I could think of, but what if I don’t even know how to check a solution efficiently?”. Typical you, griping about such minor issues when we’ve just solved all of the world’s computational problems. Fortunately, in a 2001 paper3, Marcus Hutter noted that, with a small asterisk, both of these issues can be resolved! The idea is: in addition to searching over all strings for good algorithms, also simultaneously search over all strings for correctness and time bound proofs for those algorithms! If you specify your favourite formal system, you can have your computer look at strings in order and check whether or not they represent valid proofs of a desired statement in that formal system (verifying that the proofs are valid can be done algorithmically – concretely, imagine typechecking the strings with a proof assistant like Coq or Lean). Given some formal specification of a computational problem (i.e. some formal description of what properties the output should satisfy given an input), Hutter’s algorithm does the following three things in parallel:

- Iterate through all strings in order, and check each one to see if it consists of

- code for an algorithm,

- code for a time-bound function,

- and a formal proof that the algorithm always solves the desired problem within the specified time bound. If so, add the string to a list $L$.

- Iterate through all the elements of $L$ and compute the time-bound functions to get numbers for which one we expect to finish first. This step does the same exponential weighting trick as Levin’s algorithm, spending exponentially more work on computing the finishing time for the earlier elements of $L$ than the later ones

- Among all the elements of $L$ whose time bounds we have computed numerically, run whichever one we expect to be able to finish first.

Assuming that the best time-bound is time-constructible4, this procedure achieves an asymptotic runtime as good as every provably fast and correct algorithm for the problem. In fact, Hutter showed that if you assume some stronger conditions than time-constructibility, and you spend almost all of your computation power on the 3rd of these 3 processes, his algorithm runs in time roughly $4t(n) + c$, where $t(n)$ is the infimum over the time bounds of all provably good algorithms, and $c$ is some constant. Whereas before we had a massive multiplicative constant, now we just have a massive additive constant – once we’ve done the constant work of finding the best algorithm and its proof of correctness, we can just run it.

If you step back a bit and think about what we’ve actually done, it’s maybe not that surprising that this works. You come to me and say “Nathan, I’ve been trying to figure out the optimal algorithm for my problem”, and I respond “Ah, that’s easy, I have the optimal algorithm for every problem! First, come up with the best algorithm and prove it works (this step takes constant time), and then run it on whatever input you’re dealing with”. Sure, of course this works, it’s what you were already trying to do – I’ve just described it as an algorithm. But the fact that you can describe this as an algorithm is a useful insight. To see why, let’s return to the question of matrix multiplication at the beginning of the post. I’ve seen a number of times people express the following conjecture:

For every $\epsilon > 0$, there exists an algorithm for matrix multiplication running in time $\mathcal{O}(n^{2 + \epsilon})$.

Looking at this statement, you might be unsure what exactly it entails. Is this the same as saying that there exists a single algorithm running in time $\mathcal{O}(n^{2 + o(1)})$? Or is it possible that there could exist a sequence of algorithms getting progressively closer to that bound, but that every individual matrix multiplication algorithm has runtime $\Omega(n^{2 + c})$? It turns out that, as long as we only care about algorithms for which there exist proofs of correctness and time-constructible runtime bounds (which seems reasonable – breaking this condition is very bizarre), the latter possibility can’t happen, since we know Hutter search asymptotically matches any provably good algorithm5. Even though we’d never run Hutter search on an actual computer, knowing that it exists can let us rule out this kind of thing.

That’s all for this post – thanks for reading the first installment of this blog! In the next post, I plan to address this lingering condition about time-constructibility and provable correctness – is it possible that the above statement is no longer true without those qualifiers? Tune in next time to find out!

-

I haven’t been able to find this paper except in Russian, but it’s really short so if you want you can be like me and google translate it one paragraph at a time :/ ↩

-

More formally, when the problem consists of finding an inverse of an efficiently computable function $f$ given $f(x)$, since then we can use our algorithm for $f$ to know when we’ve got the right answer. You might hear “fast way of checking solutions” and think NP, but it’s not immediately clear how this kind of algorithm could figure out that, for instance, a SAT formula was unsatisfiable. ↩

-

Which is not only well-written, but also available in English! ↩

-

Meaning that the amount of time it takes to compute a numerical value for the bound is at most equal to the bound itself. ↩

-

Ok, one somewhat slippery point that I didn’t mention was that, technically speaking, Hutter search doesn’t provably work. That is, if Hutter search is using some formal system to prove statements about programs, you can’t use that same formal system to show that Hutter search always works, because this would constitute a proof of consistency of your formal system, which is impossible by Gödel’s Second Incompleteness Theorem. But this point isn’t really that important – you seem like a smart person; I don’t think you’d ever use inconsistent axioms. ↩