Asymptotes in Asymptotics

This post is a follow-up to my last post, where I discussed variants of Universal Search and what they say about the existence of optimal algorithms. You may recall that the conclusion at the end of last time was:

If, for every $\epsilon$, there is a provably-correct matrix multiplication algorithm that provably runs in time $\mathcal{O}(n^{2+\epsilon})$, then there is an algorithm running in time $\mathcal{O}(n^{2 + o(1)})$.

More generally, for any problem, if there exists a sequence of algorithms provably achieving time bounds approaching $f(n)$, there exists one achieving $f(n)$. I think this is a somewhat satisfying thing to know, but you might still be a little unhappy. Specifically, this stipulation that the bounds be provable in our formal system seems a little slippery. All I wanted was a guarantee that there exists some asymptotically optimal algorithm, but Hutter’s algorithm only gives this restricted to programs we can reason about in ZFC or whatever.

As it turns out, this annoyance isn’t just some technical quirk about our universal search argument, but actually an unavoidable fact. That’s right, if I remove the provability clause this is no longer true!

Blum’s Speedup Theorem

Blum’s speedup theorem is a classic argument from the early days of complexity theory. Blum was interested in how to characterize the difficulty of problems – he defined a bunch of axioms for what makes sense as a complexity measure (like time or space usage). However, he also showed that no matter what complexity measure you use, there exist problems with no well-defined complexity, because any given algorithm for the problem can be “sped up” to get one performing better. As a concrete statement, we could say

Blum’s Speedup Theorem: There exists a computational problem such that, for any algorithm solving it, we can find another whose asymptotic runtime is only a square root as large1.

This is rather unnerving – we can’t talk about the complexity of such a problem as the runtime of the best algorithm for it, because there is no best algorithm! The proof of this theorem is a neat diagonalization argument, producing an entirely unnatural (but well-defined) problem.

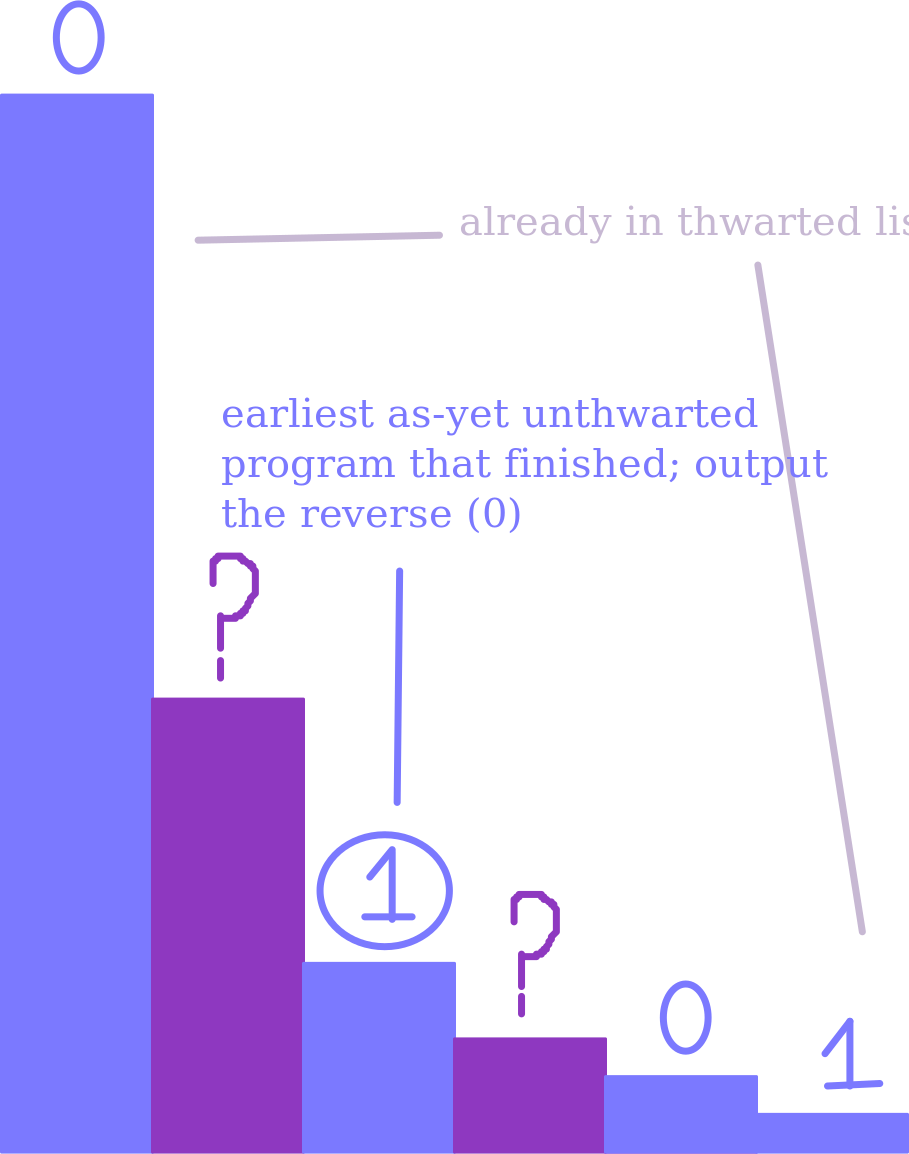

Once again, consider looking through programs in alphabetical order. The idea is to make it so that alphabetically later programs can always solve the problem asymptotically faster than alphabetically earlier ones. We’ll construct a problem where the $i$th program either gets it wrong, or needs time $2^{2^{n-i}}$ on inputs of length $n$. This problem will be a unary decision problem, meaning that the correct output is either 0 or 1 as a function of the input length. The definition of the problem on an input of length $n$ is given by the following algorithm2:

thwarted programs <- empty list

for stage s, ranging from 1 through n:

for i ranging from 1 to s:

simulate the ith alphabetical program for 2^2^(s-i) steps on a length s input

if at least one of these programs halted in the given time, and isn't already in the thwarted list:

add the first (alphabetically) such program to the thwarted list

if s = n, output the opposite of what that program said

Let’s break down what this is doing. Our goal is for this algorithm to “thwart” (i.e. output something different on some input) any program that runs in asymptotically less than $2^{2^{n-i}}$ time. When this algorithm is deciding what to output on a given length $n$, it simulates the first $n$ programs to see if any of them are finishing too quickly – if so, it finds the first one it hasn’t thwarted yet and chooses a different answer. If, for some $i$, the $i$th program runs asymptotically faster than $2^{2^{n-i}}$, this means that eventually it will always finish too early – after $i$ times finishing too early, it will definitely be thwarted. The upshot is: we’ve described something that the $i$th alphabetically program can’t do in time $2^{2^{n-i}}$.

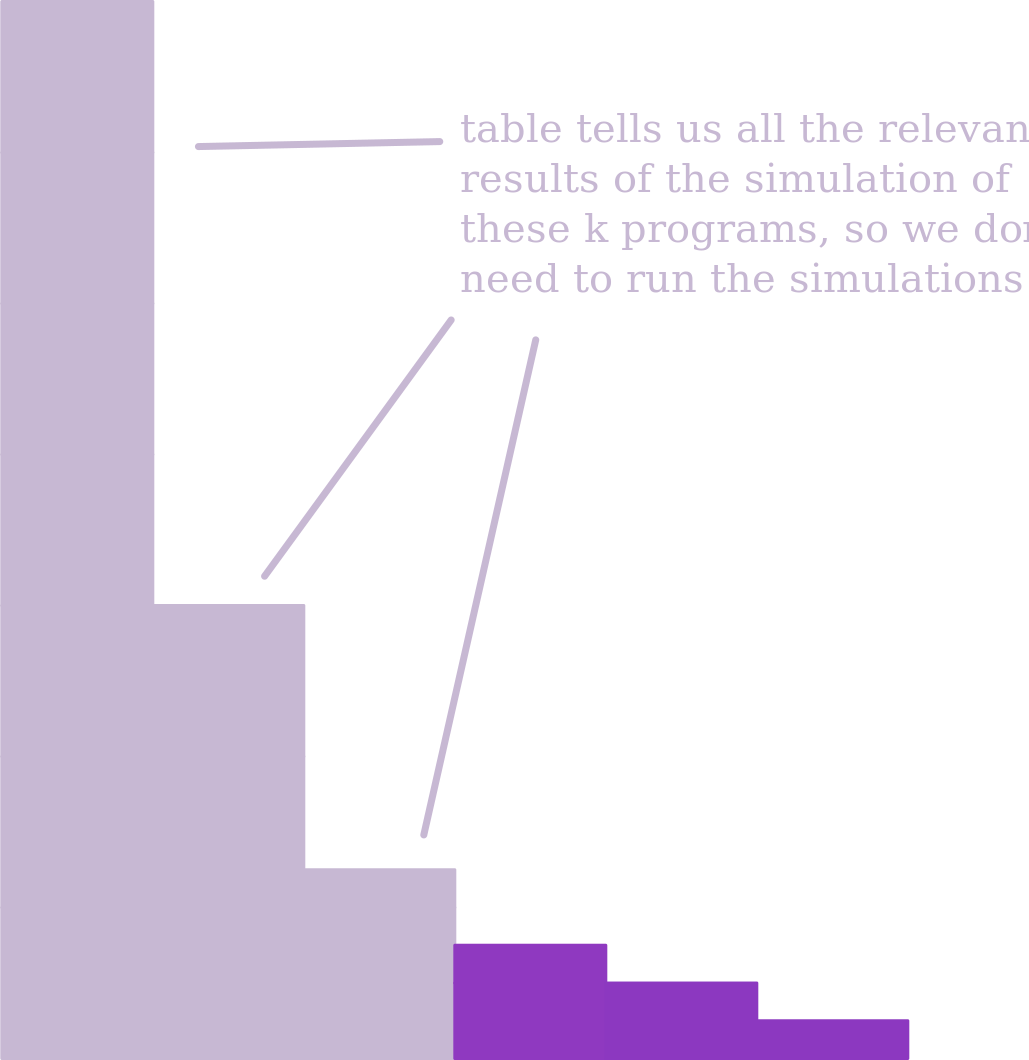

But now, I claim that for any $k$, there exists an algorithm for this problem running in time $2^{2^{n-k}}$. If we just wanted some algorithm solving the problem, we could use the one we used to define the problem – looking at the simulations this algorithm does, we find it runs in time $\mathcal{O}(2^{2^n})$. This time bound is dominated by the cost of simulating the shortest program – so, if we wanted a faster algorithm, the idea is to hard-code the simulation results for the shortest programs. That is, we run that algorithm from before, but it has a table containing, for all of the first $k$ programs,

- Whether we ever choose that program as the one to thwart

- If so, on what input we do so and what value we choose

If we know those values, we never actually need to run the simulations for the first $k$ programs, since the simulation result is only relevant on the one length when we choose that program as the one to thwart. So, hardcording this constant table of values gives an algorithm running in time $\mathcal{O}(2^{2^{n - k}})$.

This completes the proof – if we choose any given algorithm for this problem, it will be the $i$th alphabetically for some $i$, and so will need $\Omega(2^{2^{n-i}})$ time. But we can use this lookup table approach to get an algorithm running in time $\mathcal{O}(2^{2^{n-i-1}}) = \mathcal{O}(\sqrt{2^{2^{n-i}}})$. So, this is a problem with no asymptotically optimal algorithm – there’s asymptotes in the asymptotics!

Levin Search with Frievald’s Trick

This feels at first very contradictory – why doesn’t Hutter search work for that problem? The answer is that, although these faster and faster algorithms exist, we cannot prove that they’re correct when we’ve found them. Determining whether the hardcoded lookup table actually encodes whether or not each of the first $k$ programs is ever thwarted is undecidable – we know that there exists a hardcoding that correctly solves the problem, but have no way of ensuring that a given hardcoding is correct. Asymptotes in asymptotics can exist, but only when they involve programs whose properties we can’t prove.

Circling back to the question of matrix multiplication, my question is: could that happen here? Does there necessarily exist an optimal matrix multiplication algorithm, or could there be a similar situation where there’s a sequence of better and better algorithms without provable guarantees? I’m not sure if there are general results ruling out this kind of thing3, but I know that, at least if you allow randomized algorithms, there does exist an asymptotically optimal matrix multiplication algorithm.

The reason I know this is because, given two matrices and their supposed product, we can verify this fact in $n^2$ time using Frievald’s Trick, a classic randomized algorithm:

Frievald’s Trick: Given three matrices, $A$ $B$ and $C$, we can verify whether $A \cdot B = C$ with bounded error probability by choosing a constant number of random bitvectors and comparing their product with $C$ versus their product with $A \cdot B$. Both of these products can be computed in $n^2$ time (to compute $A \cdot B v$, compute $A(Bv)$)4.

In order to multiply two matrices, we can now use Levin’s algorithm, using Frievald’s trick as our verification procedure. We can repeat the simulations twice as many times for successive programs, so as to ensure that the error probability of the whole algorithm stays bounded. You can verify that, as long as we make no errors, Levin’s algorithm will still run in the asymptotically optimal runtime.

So, although we know that not every problem has a an optimal algorithm, at least matrix multiplication does. Hopefully you will sleep better at night knowing that, when people say “the matrix multiplication exponent”, they are indeed talking about something well-defined.

-

We could substitute “space” for “time” here, or talk about general complexity measures. We could also use any unbounded increasing function instead of square root. ↩

-

This proof is adapted from the one given in Dexter Kozen’s Theory of Computation. I would definitely recommend checking out that textbook – it has nice presentation, and covers a lot of stuff I haven’t seen in other complexity books. ↩

-

If you do know of such results, please let me know! ↩

-

There’s also an (in my opinion) even more slick version of this, where if we’re trying to verify a matrix multiplication over some field, we choose an extension field $\mathbb{F}$, and then instead of taking a random vector over that field we choose a random element $r$ and take $[r, r^2, \dots, r^n]$. In that case, the analysis follows from thinking of the matrix product as a polynomial over $\mathbb{F}$ and noting that it can have at most $n$ roots. ↩